As the western world continues to uncover racism hiding in plain sight I have made my own discoveries. I have been reflecting on how in all my 9 years of art education I had never studied, learnt or researched black artists. With the small exception of briefly exploring aboriginal art and a passive interest in islamic art. I painted my first black portrait only a year ago and my nude figure reference book published in New York 1998 doesn’t include one single back model. My art education is very very white.

So I have begun a study into black artists, to educate myself. I’m frankly embarrassed that after two degrees in art my knowledge and perspective is so narrow. There may be others like me who may also relate to this or generally be interested in learning more about black culture and art. So I would like to invite you on a personal journey with me as we broader our horizons and recognise the diversity of art. I am certainly not the first to write about this subject or indeed an expert, but I want to encourage other people to educate themselves and broader their understanding.

You may be wondering why we should learn more about black artists. Sadly colonialists and europeans used art to falsely justify white people being a superior race. I would really recommend watching the video below “White at the museum”, they provide an informed humours outline into the subject. Today, black artist are still not highlighted enough in education, galleries and museums. These institutes often echo the shadows of our darker past. Which is why it’s incredibly important we recognise them now.

When slaves were taken out of Africa and taken to America they were stripped of their culture as a means of controlling and suppressing them. I imagine this is why culture appropriation is such an issue today, particularly in America. Black americans have had to reclaim their heritage and history, to heal, recover and to lift themselves up. Of course they will be defensive of a culture that has been built upon decades of hardship. Especially towards those who lack a full understanding of it’s roots and see only its surface value.

I want to begin our journey in the nineteenth century with Henry Osswa Tanner.

Henry Osswa Tanner 1859-1937

Henry Osswa Tanner was born in America and was the first african-american artist to receive international acclaim. His early work explored african-american daily life, but he is most noted for his biblical depictions as well as his famous painting ‘The Banjo Lesson’.

His father was a minister and his mother a former slave who escaped via the underground railroad. When I think of art from the late 1800s I think of radical change and artistic freedom. I think of realism, true depictions of nature as it really was. I think of impressionism, colour, light and capturing the moment. I hadn’t considered that these art movements that I admired so much existed when slavery had only just been completely abolished in American in 1862. My study of art had romanticised this period and had neglected to include slavery in it’s timeline.

Tanner was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He studied at Pennsylvania Academy of fine arts, he was the only black student. He was taught by Thomas Eakins an American artist who taught his publics to study from life echoing emerging european ideas.

In 1891 Tanner moved to Paris to enjoy social and artistic freedom, escaping the racism that he had experienced in America. In paris he was inspired by Realist artists such as Gustave Courbet. In 1923 Tanner was awarded the Legion of Honour, the highest order of national merit in France.

The Banjo Lesson 1893

‘The Banjo Lesson’ 1893 Henry Ossawa Tanner

The Realism movement focused it ideology around honest and truthful depictions. Which comes across in a profound manner in this painting. Tanner has captured two african-american figures in their daily life, a subject that has been neglected in art or depicted with racist undertones. The realism within this painting portrays a genuine and intimate connection between teacher and pupil, often assumed as grandfather and grandson. A black man playing the banjo was a stereotypical image, but here Tanner handles the subject sensitively. His use of lighting adds warmth and feeling to the image. The muted background is simple and plain, drawing our eye to the two figures, but also showing us the lifestyle that these two individuals lived. Although the subject is realistic the brushstrokes are expressive, a characteristic of Tanner’s work, adding an organic and raw feeling to this painting.

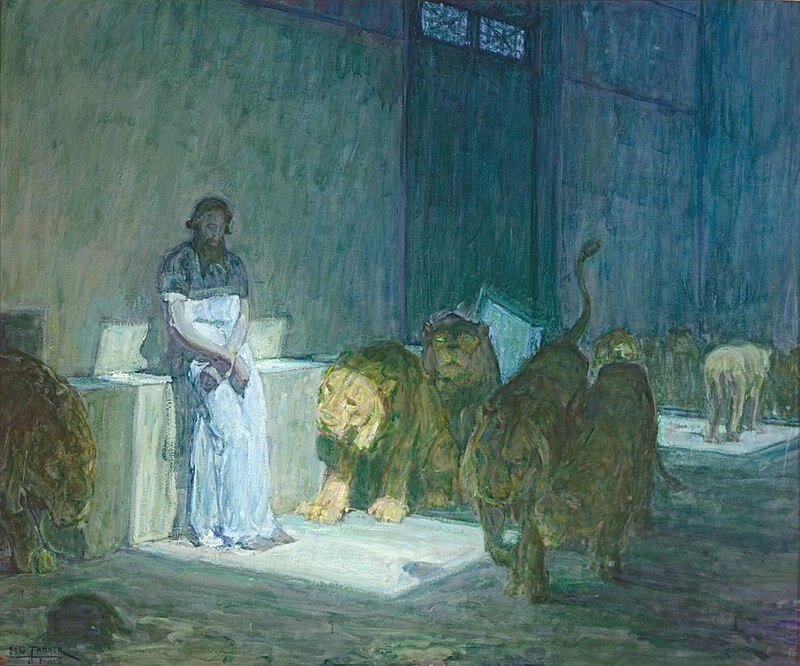

Daniel in the Lion’s Den 1907-1918 (later version)

‘Daniel in the Lion’s Ben’ 1907-1918 Henry Ossawa Tanner

In this work we see an impressionistic influence in Tanner’s use of colour and brush strokes. He depicts a miraculous moment with simplicity and calm, through his use of a cool colour palette and bare interior. He reminds us, through the subtle flash of the centre lion’s green eyes, the power and dangerous nature of the impressive beasts. He uses light not to highlight Daniel, his face is in the shadow, but the space between Daniel and a lion. Tanner is highlighting the miracle taking place. The original version of this painting gained Tanner recognition at the Paris Salon in 1896.

Tanner paved the way for other african-american artists such as Palmer Hayden. Tanner’s style was in keeping with European style and ideology, but his subject matter reflected his heritage.

Sources

https://www.oxfordartonline.com/page/african-american-art

https://study.com/academy/lesson/african-american-art-history.html

https://www.blackartinamerica.com/index.php/2018/11/20/a-very-abbreviated-version-of-black-art-history/

https://www.wikiart.org/en/henry-ossawa-tanner

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_Ossawa_Tanner

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African-American_art

https://artsandculture.google.com/usergallery/art-in-the-late-1800-s/6gKCfZBPjpu6Jg

https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/slavery

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/eapa/hd_eapa.htm

https://collections.lacma.org/node/228961